HOME > EXHIBITON > SECRET SEEKER > ABOUT

| ABOUT | WORKS | ONSITE | INTERVIEW |

SECRET SEEKER

| Curator: | Li Shengzhao |

| Artist: | Bai Qingwen, Tan Lijie, Wu Ding |

| Date: | 2015.06.28-07.27 |

| Opening: | 2015.06.28 |

| Venue: | Inna Art Space |

| Add: | Block No. 12,139 LiuHe Road, Hangzhou, China |

| Tel: | +86-0571-87023522 |

| Email: | info@innart.org |

| Organizer: | Inna Art Space |

Preface

The Chinese character for “secret” or “hidden” things (pronounced yin) alludes to those that are concealed or covered over, implying reconditeness and subtlety. According to Rene Magritte: “All visible things are concealed by their visible facets.” Hence with “reality” as our prospect, in this world, we have to search for the potential of what remains still “hidden” and “abstruse”, to let reality flex, ply and split its seams, to let it breathe.

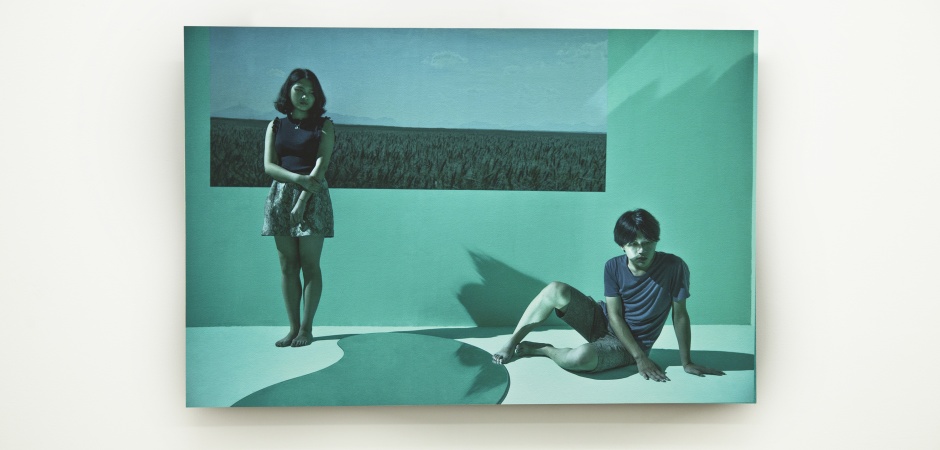

The three artists participating in the present exhibition: Bai Qingwen, Tan Lijie and Wu Ding are all graduates of the China Academy of Art (CAA)’s Studio of Experimental Video and Film. All of them work primarily with photography and image media, utilising their own, chosen means to embark upon the search for things otherwise secreted.

Bai Qingwen's video works are frequently concerned with literary texts. “Léthé” for instance relates to Baudelaire’s poem of the same name. In another work, “Former River”, certain pieces of dialogue have been lifted from Marguerite Duras’ novel “L’Amour”. For the present exhibition, the work “After I Left” is itself an adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”, narrating a man’s reminiscences and reflections on times past prior to his death. Such methods might be compared to the lin tie technique (copying from models) employed in the practice of traditional Chinese calligraphy. Here, the objective of engaging in lin (copying) is never merely reproductive, to produce a facsimile, but aims rather to “understand”, not one dimensionally or along a single trajectory, but via a more complex process, internalising and distilling the subject. On a deeper level, here the process of lin tie no longer concerns itself solely with written characters, but rather moves between text and moving imagse, fostering an exchange between the two.

more